1993年にIncome-ContingentRepayment(ICR)で始まった収入主導の学生ローン返済計画は、学生ローンの支払いを収入の特定の割合以下に制限することにより、多くの借り手にとって毎月の返済を大幅に手頃なものにすることができます。ただし、5つの収入主導型返済(IDR)プランのいずれかを検討するときは、借り手が毎月の返済費用を管理する方法だけでなく、借り手の長期的な収入の軌跡についても考慮することが重要です。支払いは収入に基づいているため、将来の高い収入を期待する人は、IDRプランを使用してもメリットがない可能性があります。支払いは収入レベルに比例して増加するため(そして返済されるローンの金利に応じて)、借り手は、より高い支払いでローンを迅速に返済するよりも、より低い月々の支払いを維持する方が良い場合とそうでない場合があります。これにより、IDRプランを選択する決定が複雑になる可能性があります。特に、連邦政府の学生ローンの返済プランの多くは、収入に対する月々の支払いを制限するだけでなく、一定の年数後に実際にローン残高の許しを引き起こす可能性があるためです。

したがって、学生ローンの債務とその潜在的な返済戦略に取り組む借り手の最初の行動は、特定の目標を特定することです。つまり、ローンをできるだけ早く全額返済し、利息費用> 途中で、またはローンの許しを求めて総支払いを最小限に抑えるために 途中で(許し期間の終わりに許される量を最大にするために)。目的が明確になると、プランナーは利用可能な返済オプションを検討できます。

ローンの許しの道を模索している人にとっては、現在の支払い義務を制限するIDRプランが望ましいことがよくあります。これは、ローンがマイナスに償却される場合でも(学生ローンの利息の発生が、借り手が比較的低所得)、そうすることは単に最終的に許しを最大化します。一方で、債務免除は最善ではないかもしれません。借り手が許しの間ずっと(通常20年または25年)そのIDR計画にとどまる場合、許された金額は税務上の収入として扱われる可能性があります(一部の借り手にとっては、実際には総費用が何よりもはるかに高くなる可能性があります彼らが実際にローン残高を$ 0に返済していたら、彼らは支払っていただろう!)

家計のキャッシュフローを管理したいという願望は、多くの場合、許しを最大化する支払いを最小限に抑えることを伴うため、最終的に重要な点は、返済戦略を慎重に選択する必要があるということです。単にできるだけ早くローンを返済するよりもコストがかかります!

Ryan Frailichは、30代のカップル、教育者、非営利団体との協力を専門とする、有料のファイナンシャルプランニングプラクティスであるDeliberateFinancesの創設者であるCFPです。プランナーになる前は、ライアンは自身が教師であり、その後、タレント&ヒューマンリソースのディレクターとしてチャータースクール組織の成長に取り組みました。彼らの年齢と職業を考えると、学生ローンは彼のクライアントの大多数にとって優先事項であるため、彼はクライアントに学生ローンのオプションに関する情報を提供する正しい方法を見つけるために何時間も費やしました。彼はTwitterで見つけることができ、ryan @ Deliberatefinances.comにメールを送信するか、基本的にはおいしい食べ物や飲み物を提供するニューオーリンズのフェスティバルで見つけることができます。

連邦政府は、さまざまな異なるプログラムの下で、何十年にもわたって教育ベースのローンを提供してきました。これらのプログラムは、一般に、いつローンが実行されたか、誰がローンを実行したか、およびローンの目的によって異なります。連邦家族教育ローン(FFEL)プログラムは、2010年まで最も一般的なローンの源泉でしたが、その後、医療と教育の和解法により、そのプログラムは段階的に廃止されました。今日のすべての連邦政府ローンは、ウィリアムD.フォード連邦直接ローンプログラムを通じて提供されており、単に「直接ローン」と呼ばれることもあります。

伝統的に、直接および/またはFFELローンを持っている借り手が学校を辞めるとき、通常、ローンの支払いがない6か月の猶予期間があります。ただし、6か月の猶予期間後、借り手は10年間の標準返済計画に置かれます。この計画では、毎月の支払いは、該当する金利で120か月にわたって償却された未払いの債務に基づいています。

ただし、多くの借り手は、10年間の標準返済スケジュールで設定された支払いを行う余裕がありません。特に学生ローンの文脈では、借り手が学校を卒業して彼らがどのような仕事をするかを知る前にローン(および支払い義務)が発生したときに「合理的な」(または実行可能な)返済義務が何であるかを決定することは難しいことを認識していますそもそも得られる(そして彼らが稼ぐ収入)。この不確実性を考慮して、政府は、管理可能な返済条件を促進するための別のオプションとして、所得主導型返済(IDR)計画を導入しました。

収入主導型返済(IDR)プランはすべて同じ前提を持っています。つまり、金利と特定の償却期間に基づいてローンの返済義務を単純に設定するのではなく、返済義務は借り手の裁量収入のパーセンテージとして計算されます(通常、調整総所得と連邦貧困ガイドラインに基づいています。

したがって、学生ローン IDRプランを追求している借り手は、毎年収入(および家族の規模)を再認定するための書類を提出する必要があり、その後、毎月のローンの支払いは、収入レベルに基づいて調整されます。これは、学生ローンの支払い義務自体が世帯にとって「実行可能」であり続けることを保証するだけでなく、そうでなければローンをデフォルトする可能性のある人々がローンを良好な状態に保ち、クレジットスコアを維持することを可能にします。

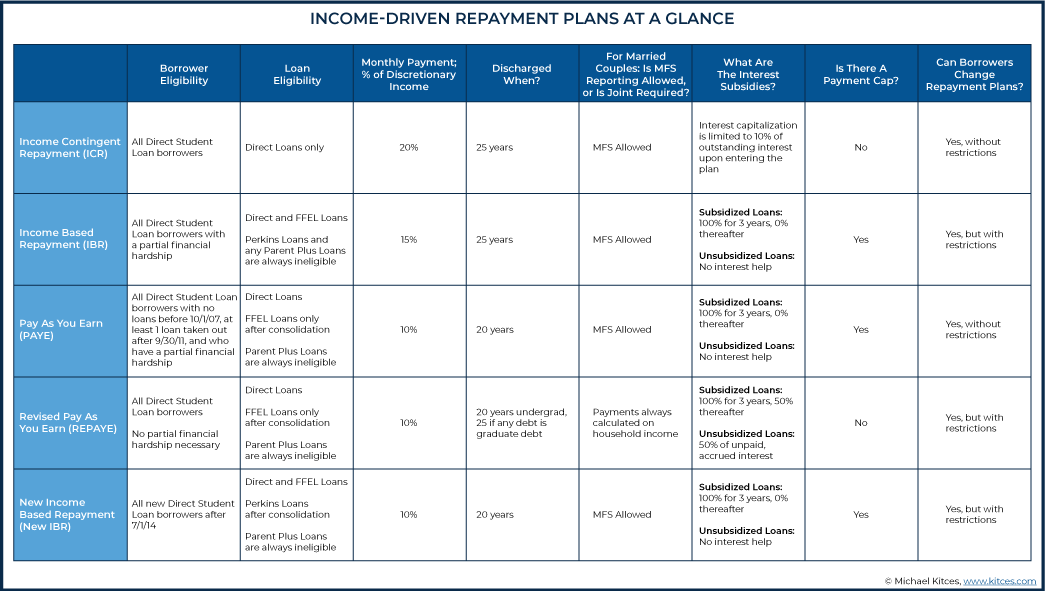

ただし、実際には、さまざまなIDRプランの個々のルールは大幅に異なり、各返済プランは8つの異なる主要な基準で異なるため、最適なIDRプランを選択するのは難しい場合があります。

前述の各基準について、各IDRプランオプションとそのルールを見てみましょう。

Income-Contingent Repayment(ICR)プランは、最初のIDRプランの1つとして1993年に開始されました。特に、他のIDRプランは、このプランが最初に到着してから借り手にとってより寛大になっているため、ICRが今日選択される返済プランになることはほとんどありません。

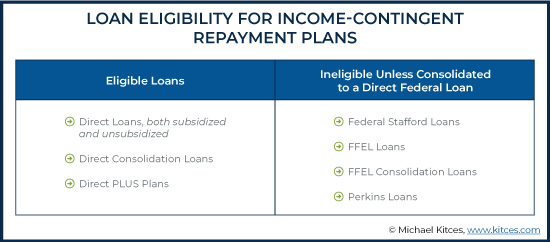

たとえば、ICRは、毎月のIDRローンの支払い額が最も高く、返済計画全体で最低レベルの利息資本に対応し、直接ローンの返済のみを許可します(ただし、連邦スタッフォードローン、FFELローン、FFEL統合ローン、およびパーキンスローンは対象外です)。 ICRのローンの種類は、直接連邦ローンに統合されている場合に適格となる可能性があります。

ただし、幸いなことに、ICRにはプランの変更に関する制限がないため、借り手がより有利な返済プランを選択するのは比較的簡単です(ただし、借り手が返済プランを変更するたびに、未払いの未払い利息は資本化されます)。

とはいえ、ICRは現在利用可能な最も寛大なプランではありませんが、ICRには収入要件がないため、他のIDRプランと比較してより多くの人々がこのプランの資格を得ることができます。

ICRの年間支払い額は、借り手の裁量収入の20%を計算することによって決定されます(ICRの場合のみ、調整総収入から借り手の家族規模の連邦貧困ラインの100%を引いたものとして定義されます)。

技術的には、借り手の収入に合わせて調整された12年間の固定ローンに基づいて支払い額を計算する別の計算が使用できますが、この方法を使用した金額は常に上記の最初のオプションよりも大きいため、実際には、この計算は次のようになります。使用したことはありません。

ただし、ICRに基づく返済額は静的ではなく、収入が増えると、ICRの月々の支払いも変わりません。 それらがどれだけ増加するかについての上限。したがって、ICRは、ローンの全期間にわたって収入が劇的に増加することを期待する借り手にとって最良の選択肢ではない可能性があります。

ICRプランでは、当初、既婚の借り手が他の世帯とは別に自分の収入だけを報告することはできませんでしたが、MFSの確定申告ステータスを使用して報告された収入を使用できるように、プランが修正されました。

ICRプランで25年間の支払いが行われた後、未払いのローン残高は免除されます。その許しは、許された金額(残りの元本とローンで発生した利息の両方を含む)の課税所得と見なされます。

ICRプランでは、プランへの最初の入力時にローンの未払い利息の最大10%を資本化する以外に、利息の補助は提供されません(これは元本のローン残高に追加されます)。

所得ベースの返済(IBR)プランは、ニーズベースの返済プランとして2007年に確立され、部分的な経済的困難の要件を初めて導入しました。借り手は、2009年7月に初めてIBRプランの使用を開始できました。

Studentloans.govのWebサイトによると、「部分的な経済的困難」は次のように定義されています。

特に、IBR計画では、「部分的な経済的困難」を、借り手がそもそも所得の割合の制限を必要とし、その恩恵を受けるほど高額の支払いを行うこと以上のものとして定義していません。

さらに、適格性に関するIBRの「経済的困難」は、裁量所得の15%を超える支払いとして定義されているため(IBRおよびICR以外のすべての返済計画の場合、裁量所得はAGIと該当する連邦貧困ラインの150%の差です。 )、任意収入の20%で支払いを制限するICRプランと比較して、ICRおよびより最近のIBRプランの対象となる人は、通常、IBRプランを選択します。

前述のように、IBRプランを使用する借り手は、部分的な財政難を抱えている必要があります。資格と返済額を決定するための2つの便利なツールはここにあります:

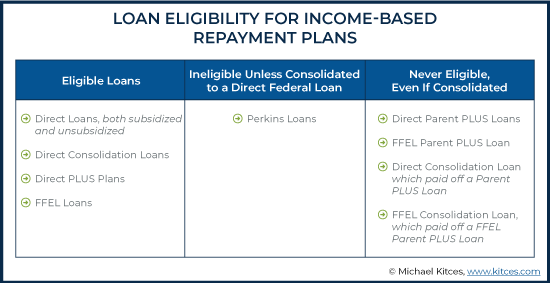

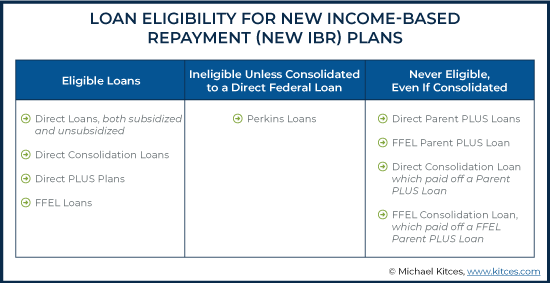

補助金付きおよび補助金なしの直接ローン、直接統合ローン、直接PLUSプラン、およびFFELローンの両方がIBRプランの対象となります。パーキンスローンは、直接ローンに統合された場合に適格となる可能性がありますが、直接ローン(つまり、親PLUSの返済に使用された直接統合ローンとFFEL統合ローン)に統合された場合でも、ParentPLUSローンは適格ではありません。ローンはIBRプランの対象にはなりません。

年間IBR支払い額の計算式は、借り手の裁量収入の15%のみに基づいており、計算に貧困ラインの150%(ICRの100%ではなく)を使用することを除いて、ICR支払いの計算式と非常に似ています。裁量収入レベル。

さらに、IBRプランの支払いは、借り手がIBRに入った時点で10年間の標準プランに入るときに支払った金額よりも大きくすることはできません。これにより、将来必要な支払いバルーンが大きくなるだけで、将来的に収入が劇的に増加するリスクが制限されます。

IBRプランでは、借り手が他の世帯収入とは別に自分の収入を報告することも許可されています。つまり、結婚している借り手がMFSステータスを申請して、1人の配偶者の収入の低いベースに収入の割合のしきい値を適用できるようにすることができます。

IBRに基づく未払いのローン残高は、25年間の支払い後に免除されます。他のすべてのIDRプランと同様に、許しの金額は課税所得と見なされます。

利子の補助金に関しては、教育省(DOE)が、補助金付きのローンの最初の3年間の未払いの未収利息をすべてカバーします。補助金なしのローンと最初の3年を超える補助金付きのローンについては、利息は補助されません。

IBRプランから別の返済プランに切り替えることを決定した借り手は、いくつかの制限に注意する必要があります。つまり、少なくとも1か月間、10年間の標準返済計画を締結する必要があります 少なくとも1回の延滞金の支払いを行います(借り手がローンを「延滞」ステータスにすることができます。これにより、一時的にローンの支払い額が効果的に減額され、その後、新しいIDRプランに切り替える前に、猶予期間中に1回の支払いが行われます)。減額された猶予金はローンサービサーと交渉することができ、潜在的に非常に低くなる可能性があります。さらに、借り手が返済計画を変更するたびに、未払いの未払いの利息が資本化されます。

Pay As You Earn(PAYE)は、大学の費用の高騰に直面している新しい借り手にいくらかの救済を提供することを目的として、2012年10月に適格な借り手に利用可能になりました(以前の多くの借り手には利用できませんでした)。

IBRプランと同様に、PAYEでも、借り手は部分的な経済的困難を抱えている必要があります(これも、指定された収入の割合のしきい値を超える学生ローンの支払いとして定義されます)。さらに、借り手は2007年10月1日の時点で未払いの学生ローン残高がなく、2011年10月1日以降に支払われた連邦学生ローンが少なくとも1つある必要があります(つまり、最近学生ローンの借り手になっている必要があります)。

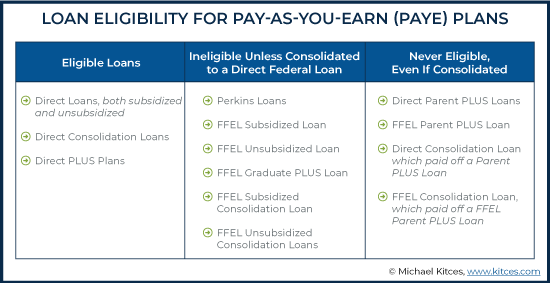

>PAYE返済プランは、補助金付きと補助金なしの両方の直接ローン、直接統合ローン、および直接PLUSプランに対応します。パーキンスローンとすべてのFFELローンは対象外ですが、直接連邦ローンに統合された場合は対象となります。FFELParentPLUSローンに加えて、Direct ParentPLUSローンとParentPLUSローンを完済した直接統合ローンも対象になりません。 PAYEプラン。

年間PAYE支払い額は、借り手の裁量収入の10%に等しく、ICR(裁量収入の20%)とIBR(裁量収入の15%)の両方よりも低くなっています。 IBRの支払いと同様に、PAYEプランの支払い額は、借り手がPAYEに参加した時点で10年間の標準プランに参加して支払った金額よりも大きくすることはできません。これにより、必要な支払いバルーンが高くなるだけで収入が劇的に増加するリスクが再び制限されます。

ICRやIBRと同様に、PAYEの借り手は、MFSのファイリングステータスを使用して収入を個別に報告できます。

PAYEの場合、ICRとIBRの両方のプランの25年間の免除期間とは対照的に、未払いのローン残高は20年間の支払い後に免除されます。許しの合計額は課税所得と見なされます。

利息の補助金は、IBRを使用する借り手と同じです。補助金付きのローンの場合、教育省(DOE)は、最初の3年間のすべての未払いの未収利息をカバーします。補助金なしのローン(および最初の3年を超える補助金付きローン)の場合、利息は補助されません。

借り手は、他の連邦返済計画に簡単に変更できます。これは、制限がなく(ICR計画からの切り替えなど)、10年間の標準計画にいつでも移行する必要がないためです。ただし、借り手が返済計画を変更するときはいつでも、未払いの未払いの利息は資本化されます。

改訂されたPayAs You Earn(REPAYE)プランは、2015年12月に借り手が利用できるようになり、PAYEの寛大な条件から利益を得ることができた適格な借り手のリストを拡張しました(少なくともICRおよびIBRプランと比較して)。 PAYEよりも支払い額が多く、許し期間が長い)。

ただし、REPAYEには、PAYEと比較していくつかの重大な欠点があります。特に、REPAYEは、既婚の借り手が世帯収入とは別に個人収入を報告することを許可しない唯一の返済計画です。借り手がMFSステータスを使用して税金を申告した場合でも、支払いは総世帯収入に基づいて行われます。これにより、REPAYEは、配偶者が彼らよりも大幅に多く稼いでいる借り手にとってはるかに魅力的ではなくなります。

「最近の」学生ローンの借り手(2011年以降に支払いがある借り手)のみが利用できるPAYEプランとは異なり、REPAYEはすべてが利用できます。 連邦政府の学生ローンの借り手は、いつローンを組んだか、または部分的な経済的困難を抱えているかどうかに関係なく。これは、2011年以前のローンを持っているためにPAYEプランの対象とならない借り手は、引き続きREPAYE返済プランに切り替えることを選択できることを意味します。

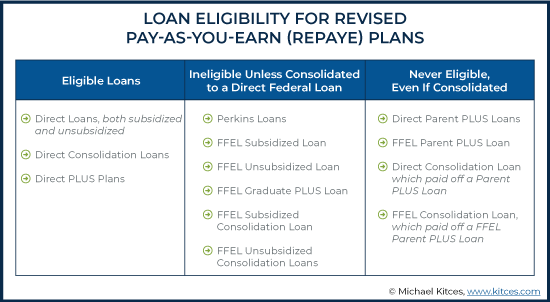

PAYEの対象となる(および対象外の)ローンは、REPAYEのローンと同じです。

REPAYEの支払い額は、PAYEの金額と同じです(借り手の裁量収入の10%)。ただし、PAYEとは異なり、増額できる支払い額に上限はないため、他の返済計画で借り手が上限を設定する場合をはるかに超えて支払いを増やすことができます。これにより、REPAYEは、将来の収益力が大幅に高い借り手にとってリスクになります(したがって、将来の支払い義務は将来の収入とともに増加し、必要に応じて将来的に許される残高を運ぶ能力が制限されます)。

REPAYEプランの場合、すべてのローンが学部ローンである場合、未払いのローン残高は20年の支払い(PAYEなど)の後に許されます。ただし、大学院ローンがある場合、許し期間は25年です(IBRやICRのように)。これらの許しの金額は課税所得と見なされます。

REPAYEプランの利子補給は、他の返済プランよりも拡大され、寛大です。補助金付きの直接ローンについては、教育省は、REPAYE計画を締結してから最初の3年間、未払いの未収利息の100%を引き続きカバーします。これはPAYEおよびIBRプラン(元のIBRプランと新しいIBRプランの両方)にも当てはまりますが、REPAYEのユニークな点は、3年後、教育省が未払いのローン利息の50%を引き続き助成しているのに対し、他のプラン(プラン入力後に利子を助成しないICRを除いて)3年後に利子の助成を提供しません。さらに、REPAYEプランは、補助金なしのローンに利息の助けを提供しない他のプランとは対照的に、補助金なしの直接ローンの未払いの未収利息の50%を補助します。

さらに、REPAYEから別の返済プランへの切り替えは、PAYE(制限なし)からの切り替えほど簡単ではありません。 REPAYEから変更する借り手は、IBRから変更する借り手と同じ制限に直面します。つまり、少なくとも1か月間10年間の標準プランを締結する必要があります 少なくとも1回の猶予金の減額を行います。繰り返しになりますが、減額された猶予金の金額はローンサービサーと交渉することができ、潜在的に非常に低くなる可能性があります。

すべての場合において、借り手が返済計画を変更するときはいつでも、未払いの未払いの利息は資本化されます。

新しいIBR計画は、2010年の医療と教育の和解法の一部として可決され、2014年に利用可能になりました。これは、必要な支払いを減らし、許しまでのタイムラインを短縮することにより、以前に利用可能だった各計画の最も寛大な側面のいくつかを組み合わせたものです。 、およびMFS税申告ステータスの使用を許可します。

ただし、これは最も借り手に優しいプランですが、のみであるため、まだ対象となる人はほとんどいません。 最近の学生ローンの借り手に適格であり、より古い学生ローンを持っている人には切り替えることができません。新しいIBRプランは、2014年7月1日の時点でローン残高がないが、古いIBRプランと同じローンの返済を提供する借り手に限定されています。

新しいIBR支払いは、支払われるべき収入の割合が低いという点で、古いIBR支払いとは異なります。古いIBRプランは、借り手の裁量収入の15%に基づいていますが、新しいIBRの支払い額は、借り手の裁量収入の10%にすぎません(PAYEおよびREPAYEの支払い額と同じ)。古いIBRプランと同様に、新しいIBRプランは、借り手がプランに入った時点で10年標準プランに入るときに支払った金額よりも大きくすることはできず、収入レベルの増加に伴って返済額が劇的に増加するリスクを制限します。

>新しいIBRプランの場合、未払いのローン残高は20年の支払い後に免除されます。これは、古いIBRで必要とされる25年よりも短い期間です。その許しは課税所得と見なされます。

利子補給に関しては、当初のIBR計画と同じです。教育省は、助成されたローンの最初の3年間のすべての未払いの未収利息をカバーします。補助金なしのローン、および最初の3年を超える補助金付きのローンについては、利息の援助はありません。

新しいIBRからの切り替えを希望する借り手は、少なくとも1か月間10年間の標準プランを締結する必要があります ローンサービサーと交渉することができる(そして潜在的に非常に低くなる可能性がある)少なくとも1つの減額された猶予金を支払います。 Any outstanding, unpaid interest when switching plans will be capitalized.

Given all the variation in rules across IDR plans, required minimum payments can vary significantly depending on the situation.

Let’s look at an example.

Corey the Attorney

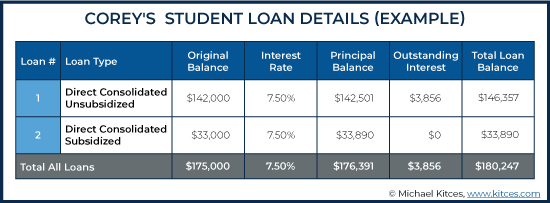

Corey is a young attorney with a current student loan balance consisting of $176,391 principal + $3,856 interest =$180,247 at a 7.5% annual interest rate.

After graduating, Corey could not afford the required payments under the 10-Year Standard Plan and switched to a REPAYE plan. Upon doing so, his outstanding loan interest was capitalized and added to his principal balance.

Corey suspects that REPAYE might not be the best plan for him, and seeks help from his financial advisor to determine what his best course of action would be to manage his loan repayments most effectively.

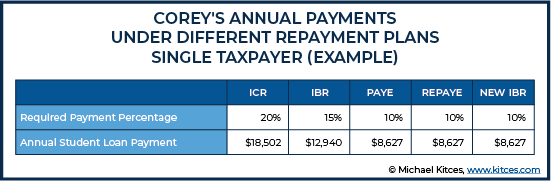

Corey earns an annual salary of $120,000. After his 401(k) contributions and other payroll deductions, his AGI is $105,000. Based on the state in which Corey lives, 150% of his Poverty Line (for a family size of 1) is $18,735, which means his discretionary income is $105,000 - $18,735 =$86,265.

Under Corey’s original 10-Year Standard Repayment plan, Corey was required to make annual payments of $24,924. Under the IDR plans, however, his monthly payments would be significantly lower, with forgiveness of the outstanding balance after 20-25 years.

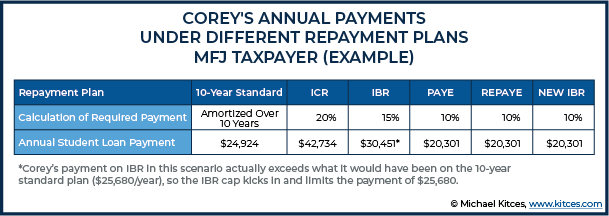

The table below shows Corey’s annual payments for each of the IDR plans:

The range of payments available to Cory across the plans is substantial, more than $8,600 in the first year alone (between $17,253 for ICR and $8,627 for PAYE, REPAYE, and the New IBR plans), assuming that he is eligible for all options, which may not always be the case. Notably, as the plans become more current, they also become more generous with lower payment obligations.

Corey has indicated that he plans to marry and adopt a child in the next year and that his soon-to-be spouse currently has an AGI of $130,000. With the larger income and larger family size, his options are updated as follows, assuming the family will be filing their taxes jointly:

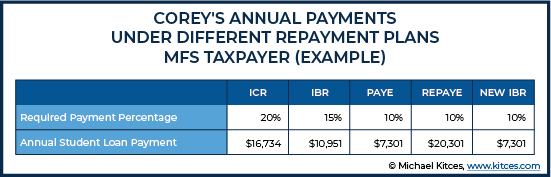

While the gap between IBR and the other options is starting to grow, using MFS as a tax-filing status can reduce his payments for some of the plans even further. If Corey were to use an MFS Status, his options would be as follows:

Here we see where the inability to use MFS with REPAYE can be harmful to someone who is about to get married, as staying on REPAYE would require joint income to be used to calculate discretionary income, resulting in a substantially higher required payment.

While the New IBR option is very appealing, upon checking Corey’s loan records, his advisor discovers that some of his loans originated before 2014, which excludes him from eligibility as borrowers using New IBR may not have any loan balances prior to July 2014.

Thus, payments on IDR plans for Corey will initially range from $7,301 (under PAYE filing MFS) to $42,734 (using ICR filing MFJ) in annual payments. While this would be the expected range for at least the first few years of the repayment plan, life events pertaining to family size, tax filing status, and income levels can come up that may impact Corey’s student loan repayment amounts.

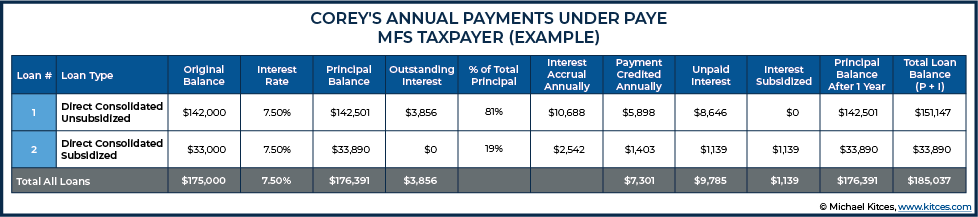

At first glance, it seems clear that Corey should use PAYE and file MFS next year since that would produce the lowest possible monthly payment. But that could have a significant downside since interest accrual will be larger every year than the required payments if he were to choose PAYE. Which plays out into what is known as “negative amortization”, where the principal-and-interest balance amortizes higher as the excess unpaid interest accrues and compounds.

Under normal student loan rules, required payments get split and applied to loans in proportion to the total balance owed. So, in this case, the required payment of $7,301 annually will be applied 81% to the unsubsidized loan, and 19% to the subsidized loan.

If Corey elects to use PAYE and MFS as a tax status, he’ll see his smaller, subsidized student loan principal stay steady in years 1-3 due to the PAYE interest subsidy, but the larger, unsubsidized loan balance will have grown, and his payments of $7,301 this year will have resulted in a balance $4,790 greater than a year ago. Beyond the first 3 years, the interest subsidy is lost, and he’ll see his balance grow for both of the loans.

If his future income growth is low, this plan might make sense, as it would keep his monthly payments low. Using assumptions of 3% income growth and federal poverty level growth, and staying on this exact plan for 20 years, the total principal + interest at forgiveness is $315,395. If we apply a 30% effective tax rate, he will incur just under $95,000 of taxes. If we add the $95,000 of taxes to the $196,000 of payments he made over 20 years, we get to a total loan cost of $290,786.

Corey’s financial advisor compares these numbers to privately refinancing the debt to get a better interest rate. If Corey is approved for a 15-year loan at a 5% interest rate, his monthly payments would be $1,425 with a total loan cost of $256,568. With the help of his advisor, Corey determines that the monthly payment amount under this refinanced loan can be comfortably paid amongst other goals and chooses to pursue the 15-year private refinance option. Under this plan, Corey will pay down the debt sooner (15 years, versus 20 years under PAYE filing MFS until forgiveness) and will pay less in total costs along the way. In addition, he can eliminate the uncertainty (and anxiety) of seeing a constantly growing loan balance, and actually see progress to $0 being made along the way.

Negative amortization isn’t necessarily a deal-breaker. It goes back to whether the intention is to pay off the loan in full, or, to go for some form of forgiveness. In reality, for those who do plan to aim for forgiveness, it actually makes sense for the borrower to do everything they can to minimize AGI, not only resulting in lower student loan payments but also having a higher balance forgiven. This can make sense both for Public Service Loan Forgiveness (PSLF), where the balance is forgiven after 120 payments (10 years) and is not taxable and also for a borrower going towards the 20- or 25-year forgiveness available under one of the IDR plans.

I regularly see people who make $50,000 - $70,000 per year with loan balances over $100,000. For a resident physician, who will see their income dramatically rise, an IDR plan (usually PAYE or REPAYE) makes sense to make payments manageable while in residency, even if it means a small amount of negative amortization on their loans. Their ability to repay the loans once they have their full doctor salary means that going for long-term forgiveness rarely makes sense, but the IDR plan can help them manage cash flow during the tight income years as a resident for a relatively modest cost (of negatively amortized interest).

Many borrowers with early-career income levels similar to a resident may not have the same expectations for substantial long-term earnings growth in their future. For these individuals, pursuing long-term forgiveness using an IDR plan may be a more advantageous option. In other words, negative amortization isn’t just used to incur a small amount of interest to be repaid in the future when income rises, but a potentially larger amount of negatively amortizing interest that will ultimately be forgiven altogether.

別の例を見てみましょう。

Shannon the Acupuncturist

Shannon is a 28-year-old who runs her own acupuncture business. Other important details about her situation include:

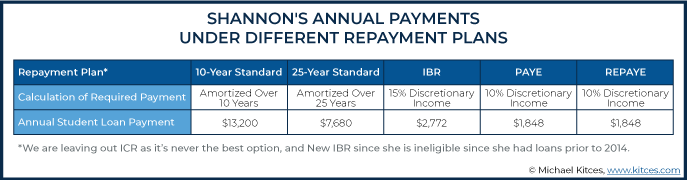

Here are her repayment options:

The 10-Year Standard plan would require her to pay $13,200 annually (over $1,100/month), which is clearly not feasible. She could instead choose to repay with a 25-Year Standard Repayment plan, but Shannon would end up paying nearly $192,000 over that time and the $640 monthly payment would also be infeasible unless she stopped contributing to retirement accounts.

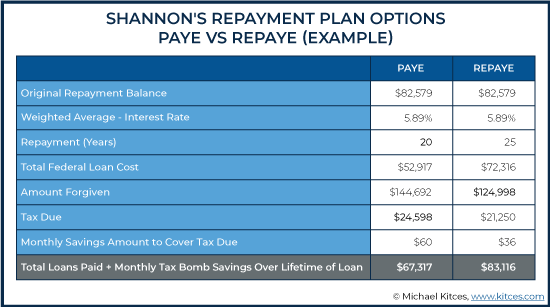

Since she is eligible for PAYE and REPAYE, neither IBR nor ICR makes sense, as each has higher required payments. So, she will decide between PAYE or REPAYE, each of which requires her to pay 10% of her Discretionary Income, or $154 per month at her current income level.

The interest subsidies on REPAYE are better, as while both PAYE and REPAYE will subsidize 100% of Shannon's unpaid interest on her loan during the first three years of the plan, REPAYE will continue to subsidize 50% of unpaid interest afterward whereas PAYE will not subsidize interest after three years. Thus, the growth of Shannon’s balance due to an increasing interest balance will be limited with REPAYE.

Using PAYE, however, will result in loan forgiveness in 20 years instead of in 25 years under REPAYE.

Either way, the so-called ‘tax bomb’ must also be accounted for, since the forgiven loan balance will be treated as taxable income received in the year the loan is forgiven. Borrowers pursuing any IDR plan should plan to cover that tax, and in this case, Shannon can do so with relatively small monthly contributions to a taxable account.

To sum it all up, to repay her loans in full on a 25-Year Standard Repayment plan, Shannon likely would have to pay $640 per month, at a total repayment cost of $192,000.

On REPAYE, she would start with payments of $154/month based on her Discretionary Income and, factoring for inflation, top out in 25 years at $343/month. She would owe a total repayment amount of $72,316 in loan costs + $21,250 in taxes =$93,566.

If she chooses PAYE, she would have starting payments of $154/month (also rising to $295 with AGI growth over 20 years), with a total repayment amount of $52,917 in student loan costs + $24,598 in taxes =$77,515. She would also finish in 20 years (versus 25 years on REPAYE).

Assuming all goes as planned, PAYE appears to be the better choice, as even though REPAYE provides more favorable interest subsidies, Shannon’s ability to have the loan forgiven 5 years earlier produces the superior result.

But what if her situation changes, as life does tend to happen that way?

If Shannon got married, and her spouse made substantially more than her, she may have to use MFS to keep her payments lower, and thus lose out on any income tax benefits available filing as MFJ.

Shannon also runs the risk of having to repay a higher balance in the future if she switches careers; in this situation, using PAYE for the 20-year forgiveness benefit would no longer make sense. Say she takes a new job resulting in AGI of $110,000 annually, and she takes that job 5 years into being on the PAYE plan.

Instead of repaying the original balance she had at the outset of opting into the PAYE plan, she would need to pay back an even higher balance due to growth during the years on PAYE, when payments were smaller than interest accrual resulting in negative amortization. As her salary rises, her payments would also rise so substantially (up to $747 here), that her total repayment cost to stay on PAYE for 15 additional years would actually be more than it would be to simply pay the loan off.

If she decides to reverse course and pay off the loan balance instead of waiting for forgiveness, she might instead benefit from a private refinance if she can get a lower interest rate, since that now once again becomes a factor in total repayment costs.

In the end, IDR plans have only been recently introduced, and as such, there is very little historical precedent regarding their efficacy for relieving student loan debt, particularly with respect to the income tax ramifications of student loan debt forgiveness. As in practice, ICR has rarely been used for loan forgiveness (difficult as the percentage-of-income payment thresholds were typically high enough to cause the loan to be repaid before forgiveness anyway), and the other IDR plans have all been rolled out in the past decade.

Accordingly, we won’t see a critical mass of borrowers reaching the end of a 20- or 25-year forgiveness period until around 2032 (PAYE) and 2034 (IBR). And will then have to contend for the first time, en masse, with the tax consequences of such forgiveness. Though forgiven loan amounts are taxable income at the Federal level, it is notable that Minnesota has passed a law excluding the forgiven amount from state taxes.

Similar to other areas of financial planning, it’s prudent to plan under the assumption that current law will remain the same, but also to be cognizant that future legislation may change the impact of taxable forgiveness. By planning for taxation of forgiven student loan debt, advisors can help their clients prepare to pay off a potential tax bomb; if the laws do change to eliminate the ‘tax bomb’, clients will have excess savings in a taxable account to use or invest as they please.

IDR plans are complex but offer many potential benefits to borrowers with Federal student loans. Thus, it is critical for advisors to understand the various rules around each plan to recognize when they might be useful for their clients carrying student debt. The benefits vary significantly, and depending on a borrower’s situation, IDR plans may not even make sense in the first place. But for some, using these plans will offer substantial savings over their lifetimes. Despite the uncertainty surrounding these repayment plans, they remain a crucial tool for planners to consider when assessing both a client’s current-day loan payments and the total cost of their student loan debt over a lifetime.